Cognitive impairment from severe COVID-19 equivalent to 20 years of aging, study finds

Cognitive impairment as a result of severe COVID-19 is similar to that sustained between 50 and 70 years of age and is the equivalent to losing 10 IQ points, say a team of scientists from the University of Cambridge and Imperial College London.

31 may 2022--The findings, published in the journal eClinicalMedicine, emerge from the NIHR COVID-19 BioResource. The results of the study suggest the effects are still detectable more than six months after the acute illness, and that any recovery is at best gradual.

There is growing evidence that COVID-19 can cause lasting cognitive and mental health problems, with recovered patients reporting symptoms including fatigue, 'brain fog', problems recalling words, sleep disturbances, anxiety and even post-traumatic stress disorder (PTSD) months after infection. In the UK, a study found that around one in seven individuals surveyed reported having symptoms that included cognitive difficulties 12 weeks after a positive COVID-19 test.

While even mild cases can lead to persistent cognitive symptoms, between a third and three-quarters of hospitalized patients report still suffering cognitive symptoms three to six months later.

To explore this link in greater detail, researchers analyzed data from 46 individuals who received in-hospital care, on the ward or intensive care unit, for COVID-19 at Addenbrooke's Hospital, part of Cambridge University Hospitals NHS Foundation Trust. 16 patients were put on mechanical ventilation during their stay in hospital. All the patients were admitted between March and July 2020 and were recruited to the NIHR COVID-19 BioResource.

The individuals underwent detailed computerized cognitive tests an average of six months after their acute illness using the Cognitron platform, which measures different aspects of mental faculties such as memory, attention and reasoning. Scales measuring anxiety, depression and post-traumatic stress disorder were also assessed. Their data were compared against matched controls.

This is the first time that such rigorous assessment and comparison has been carried out in relation to the after effects of severe COVID-19.

COVID-19 survivors were less accurate and with slower response times than the matched control population—and these deficits were still detectable when the patients were following up six months later. The effects were strongest for those who required mechanical ventilation. By comparing the patients to 66,008 members of the general public, the researchers estimate that the magnitude of cognitive loss is similar on average to that sustained with 20 years aging, between 50 and 70 years of age, and that this is equivalent to losing 10 IQ points.

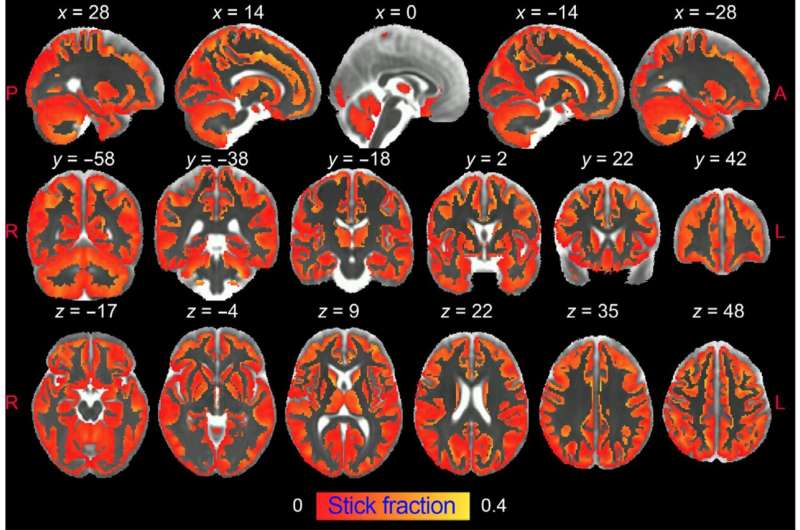

Survivors scored particularly poorly on tasks such as verbal analogical reasoning, a finding that supports the commonly-reported problem of difficulty finding words. They also showed slower processing speeds, which aligns with previous observations post COVID-19 of decreased brain glucose consumption within the frontoparietal network of the brain, responsible for attention, complex problem-solving and working memory, among other functions.

Professor David Menon from the Division of Anaesthesia at the University of Cambridge, the study's senior author, said: "Cognitive impairment is common to a wide range of neurological disorders, including dementia, and even routine aging, but the patterns we saw—the cognitive 'fingerprint' of COVID-19—was distinct from all of these."

While it is now well established that people who have recovered from severe COVID-19 illness can have a broad spectrum of symptoms of poor mental health—depression, anxiety, post-traumatic stress, low motivation, fatigue, low mood, and disturbed sleep—the team found that acute illness severity was better at predicting the cognitive deficits.

The patients' scores and reaction times began to improve over time, but the researchers say that any recovery in cognitive faculties was at best gradual and likely to be influenced by a number of factors including illness severity and its neurological or psychological impacts.

Professor Menon added: "We followed some patients up as late as ten months after their acute infection, so were able to see a very slow improvement. While this was not statistically significant, it is at least heading in the right direction, but it is very possible that some of these individuals will never fully recover."

There are several factors that could cause the cognitive deficits, say the researchers. Direct viral infection is possible, but unlikely to be a major cause; instead, it is more likely that a combination of factors contribute, including inadequate oxygen or blood supply to the brain, blockage of large or small blood vessels due to clotting, and microscopic bleeds. However, emerging evidence suggests that the most important mechanism may be damage caused by the body's own inflammatory response and immune system.

While this study looked at hospitalized cases, the team say that even those patients not sick enough to be admitted may also have tell-tale signs of mild impairment.

Professor Adam Hampshire from the Department of Brain Sciences at Imperial College London, the study's first author, said: "Around 40,000 people have been through intensive care with COVID-19 in England alone and many more will have been very sick, but not admitted to hospital. This means there is a large number of people out there still experiencing problems with cognition many months later. We urgently need to look at what can be done to help these people."

Professor Menon and Professor Ed Bullmore from Cambridge's Department of Psychiatry are co-leading working groups as part of the COVID-19 Clinical Neuroscience Study (COVID-CNS) that aim to identify biomarkers that relate to neurological impairments as a result of COVID-19, and the neuroimaging changes that are associated with these.